A general investigation of the factors associated with currency returns.

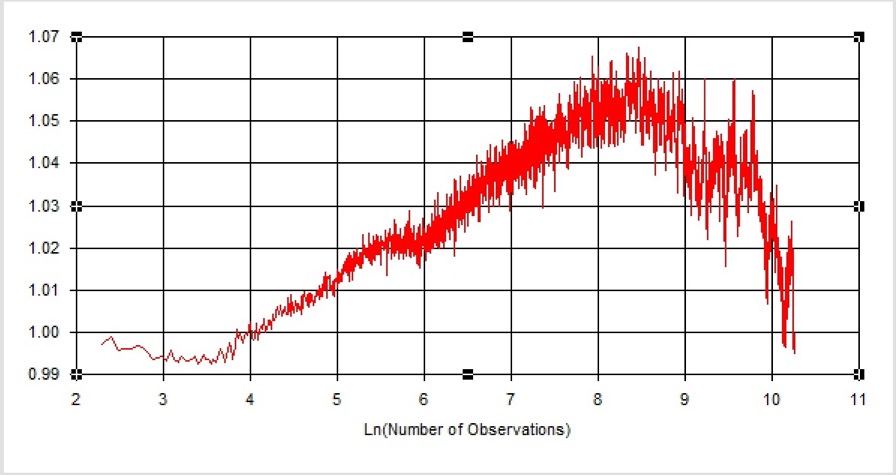

Implicit within any statement referring to “long term” returns is the assumption of some characteristic scale. This assumption can be tested with rescaled range analysis.

The chart above is produced from a composite of exchange rates including 114076 daily returns. The range of returns grows at a greater rate than expected from approximately 2 months until moderating at around 1 year and turning down after approximately 10 years. This is consistent with the body of research into PPP equilibrium that has suggested multi-year average reversion times. Consistent with this we will examine non overlapping 1 month, 6 month and 5 year returns from 1988-06-30 until 2021-06-30. We will divide the sample into two sub samples representing the pre and post GFC market regimes.

Forward Rate Bias

Popularly referred to as the carry trade by practitioners and the subject of a rich academic literature attempting to explain this empirically observed and persistent breakdown of uncovered interest rate parity. The implementation of this strategy in FX markets is simply a matter of borrowing low interest currencies and placing the funds into high interest currencies. This strategy was so persistently effective that despite the logical inconsistencies many market participants began to believe that it was in fact a “free lunch”. The effectiveness of the strategy has been degrading since at least the period around the GFC.

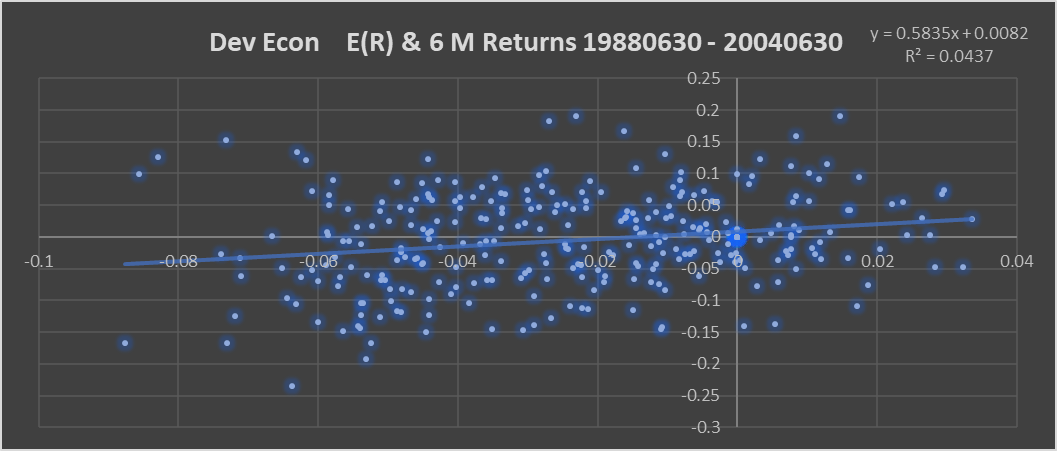

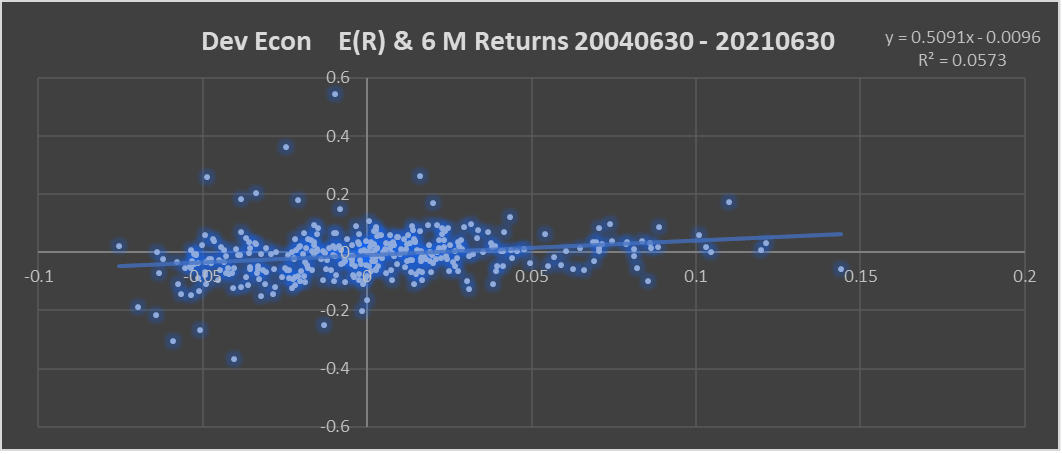

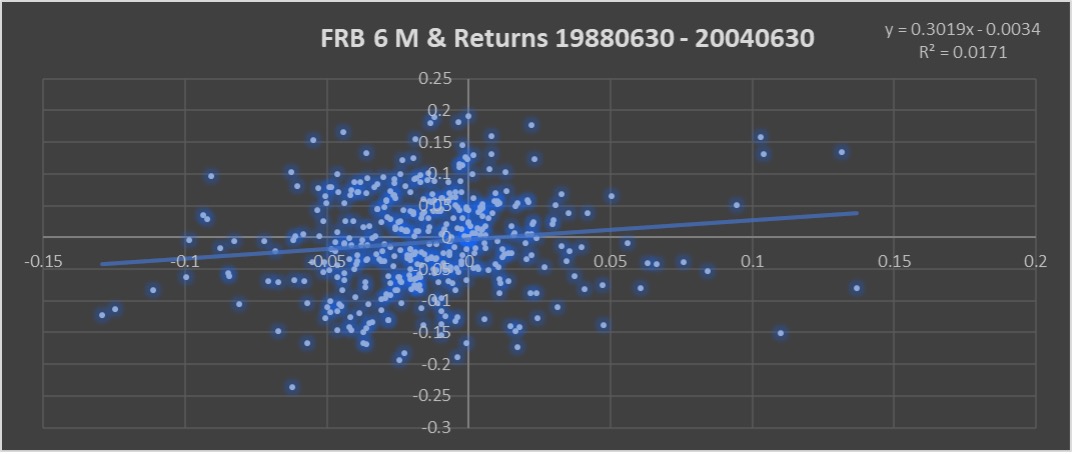

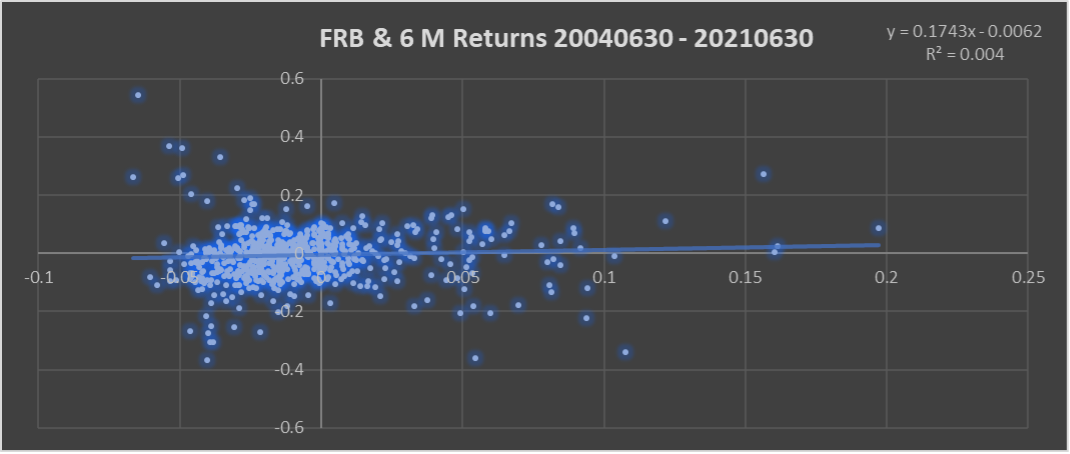

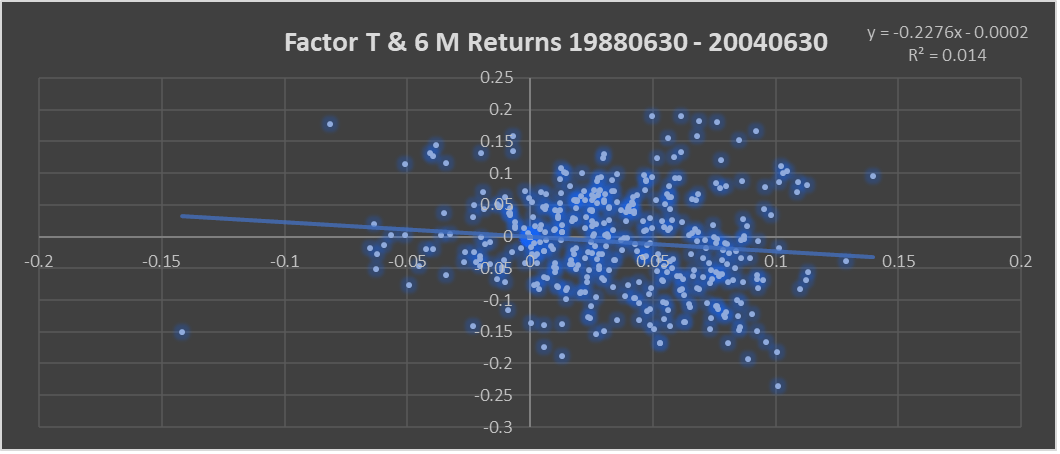

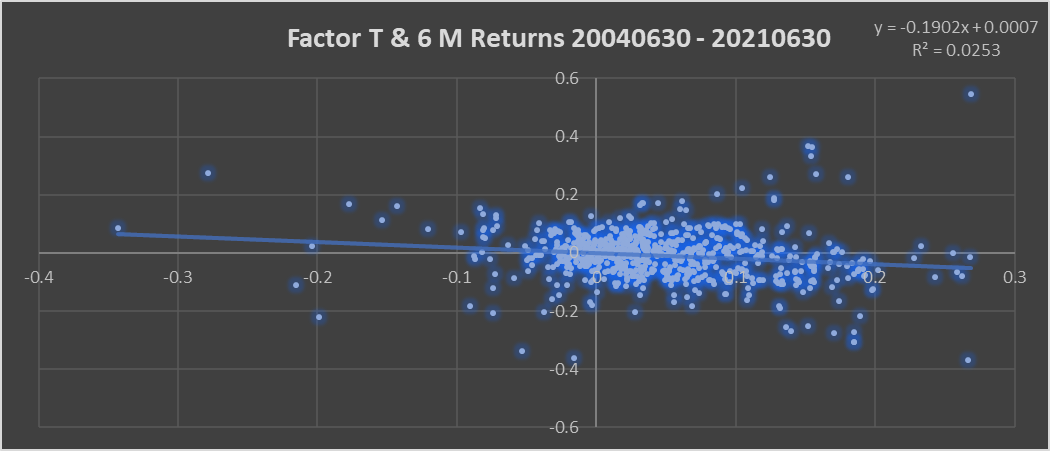

The following charts are scatter plots comparing subsequent 6 month returns with the overnight interest rate differential at the beginning of the period. Assuming that uncovered interest rate parity holds means that the coefficient should be zero.

The historical effectiveness of the strategy is clear in the first period examined before the GFC

Post GFC the relationship has broken down.

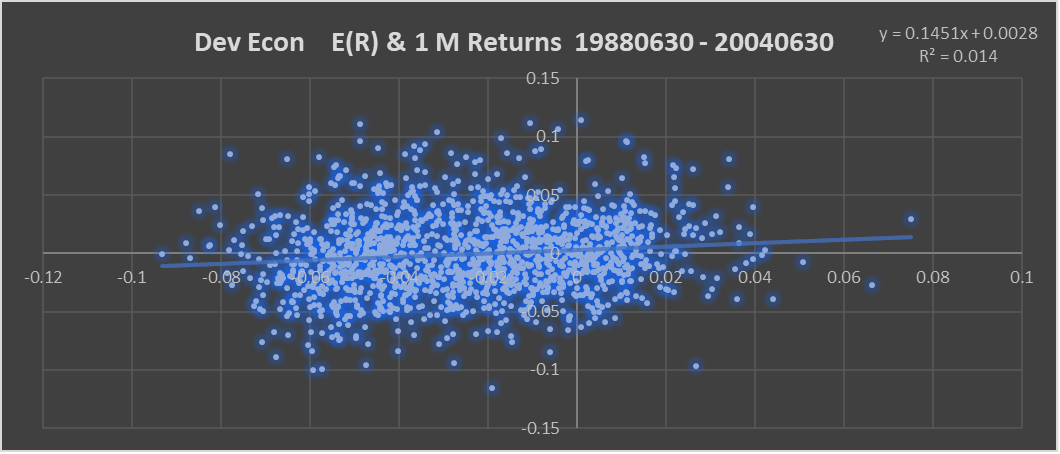

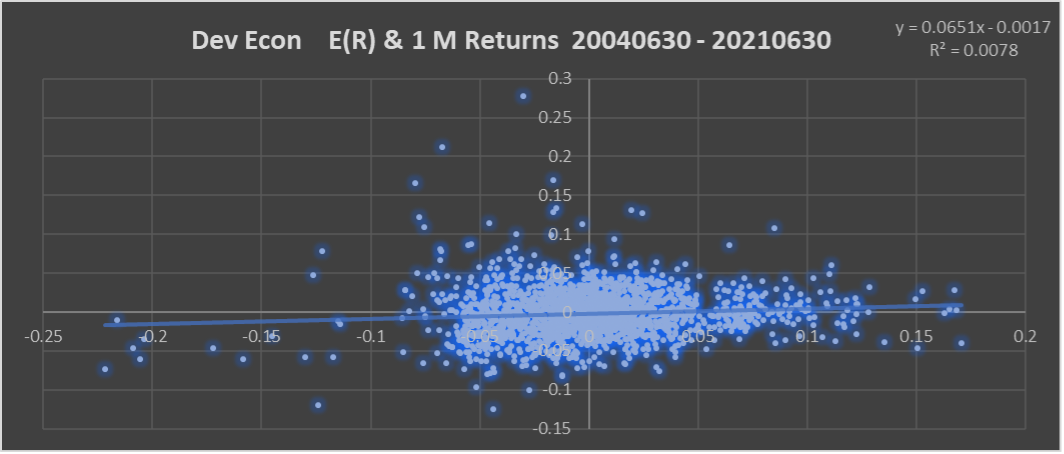

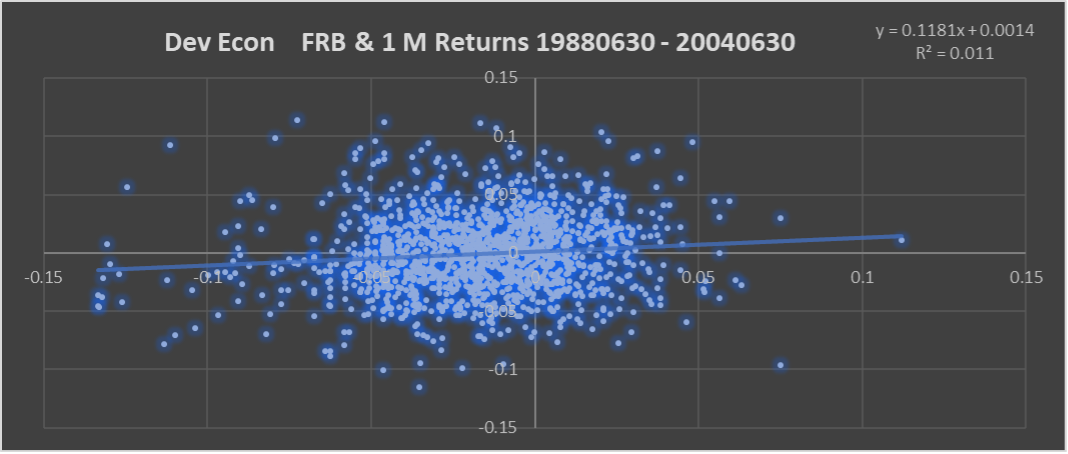

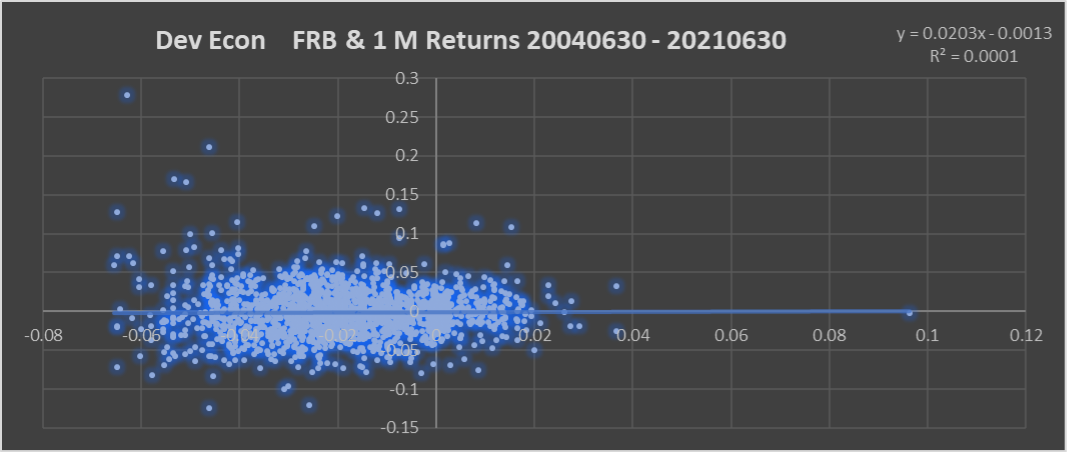

If we restrict our analysis to developed economies only and 1 month returns, we find the same result. This is representative of the most popular way this factor strategy has been implemented.

It is the view of CLCI that the FRB has historically proxied for a risk factor that has not necessarily manifested in the relatively short run of historical return data that investors have been exposed to. Events such as sudden devaluations and regime changes.

The events of the GFC have led to unprecedented central bank manipulation of interest rates and this may have caused the breakdown of the FRB signal.

CLCI proposes that a more suitable proxy may now be a measure of asymmetric risk derived from the relative return distributions. Specifically, we find that currencies that tend to fall in value as cross rate return standard deviation rises provide a return premium. This is a relationship that has persisted beyond the GFC. This is proprietary research, and we refer to this measure as Factor T.

Froot, K. A. and R. H. Thaler (1990), "Anomalies: Foreign Exchange", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4, 179-92.

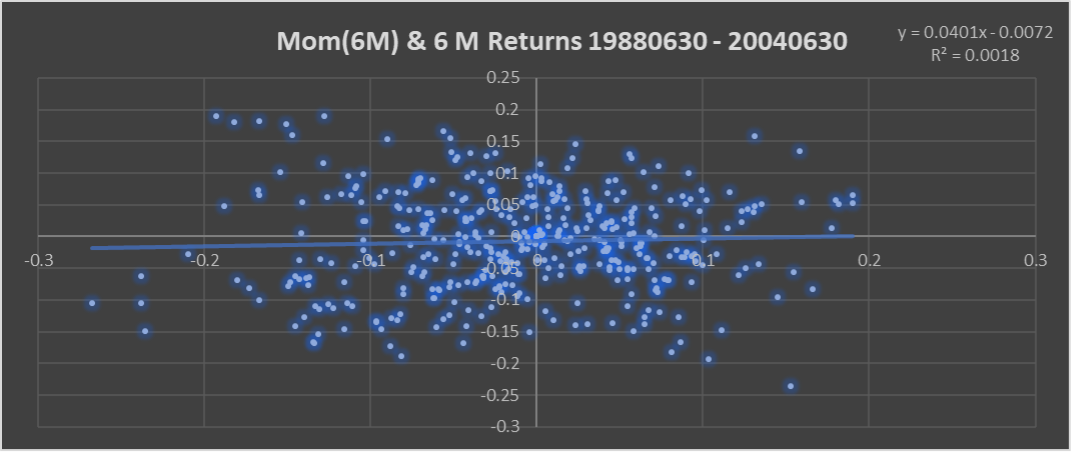

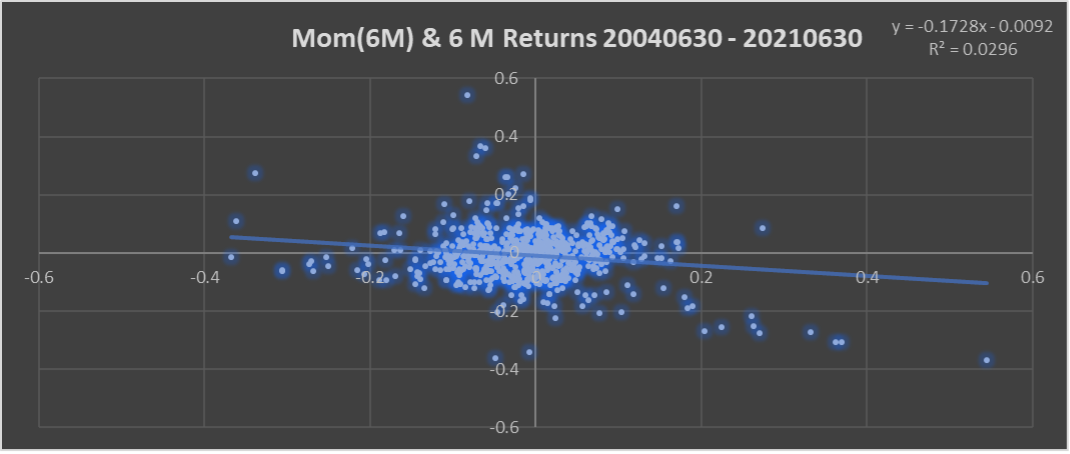

Momentum

The momentum effect has been a persistent anomaly observed across asset classes and has been studied extensively. The effect can be explained by investor under-reaction and subsequent over-reaction to news exacerbated by hierarchical information cascade. Consistent with the literature we find that the momentum effect in currencies has been largely confined to developing markets and has weakened or reversed for most formation periods in the latter half of the sample data. As markets become more liquid and arbitrage and trading costs are reduced it can be expected that momentum effects will be dominated by other factors.

Burnside, C.; Eichenbaum, M.; and Rebelo, S. (2011), “Carry trade and Momentum in currency markets”, Annual Review of Financial Economics 3(1), 511–535.

Menkhoff, L., Sarno, L., Scmeling, M. and Schrimpf, A., (2012). “Currency Momentum Strategies”, Journal of Financial Economics, (forthcoming).

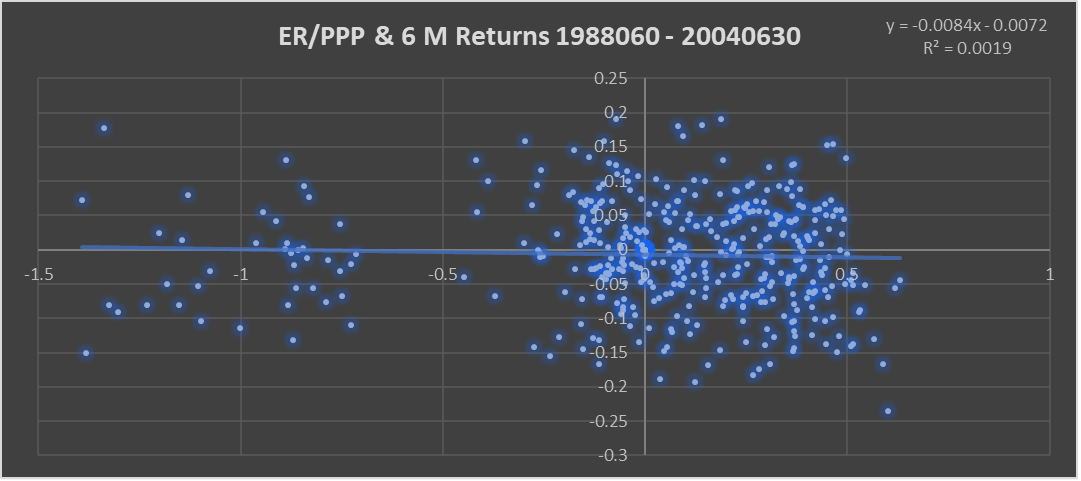

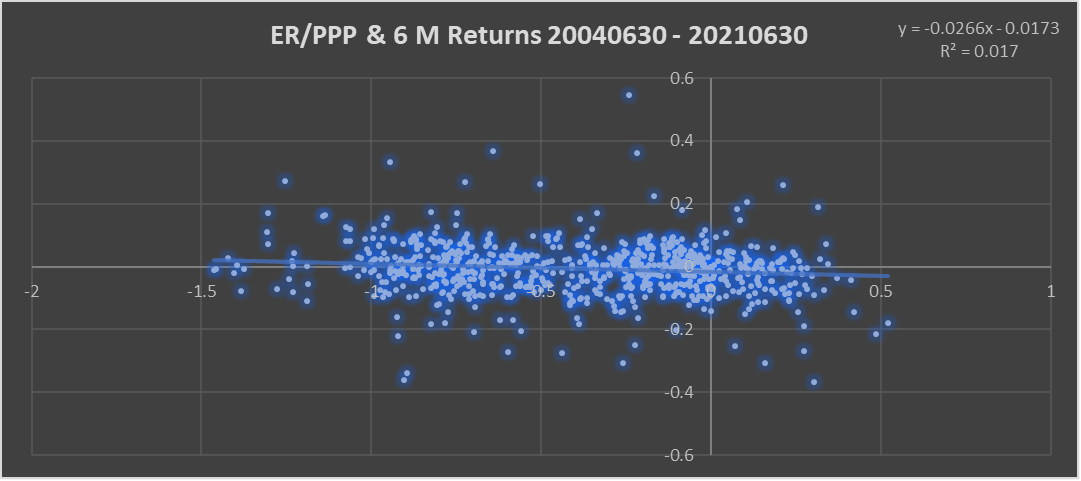

Value

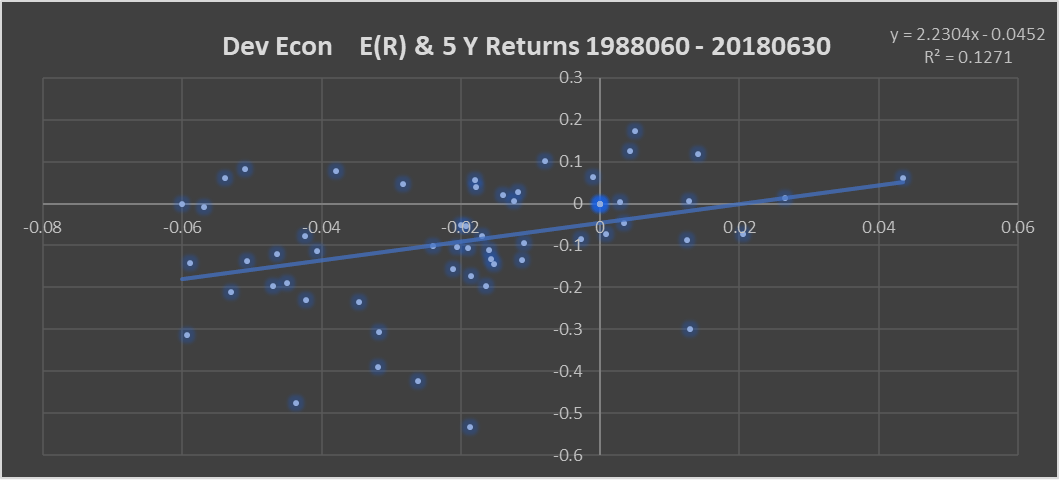

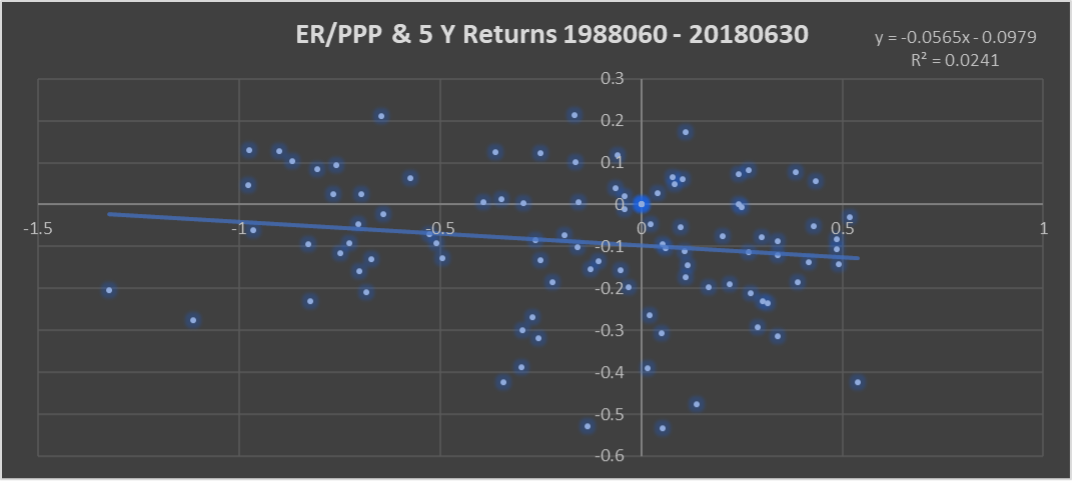

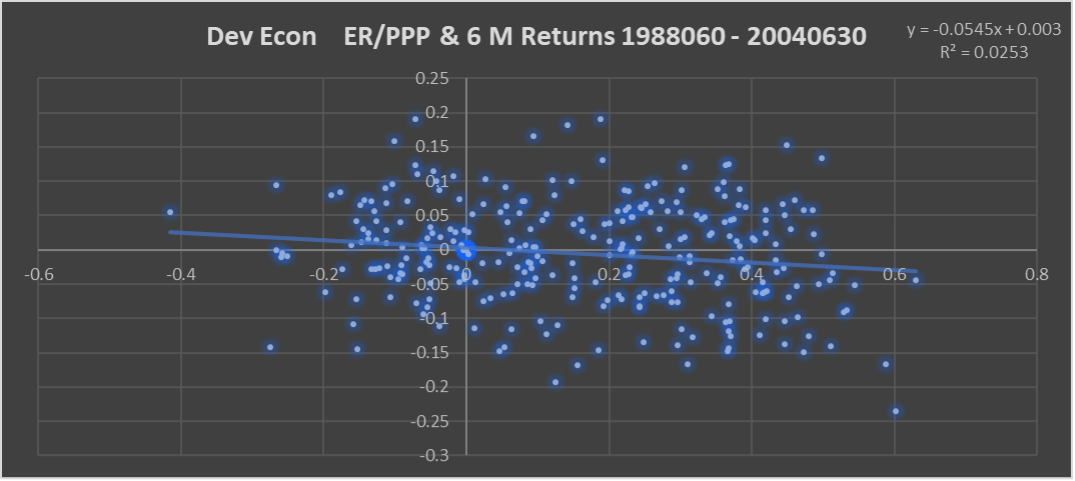

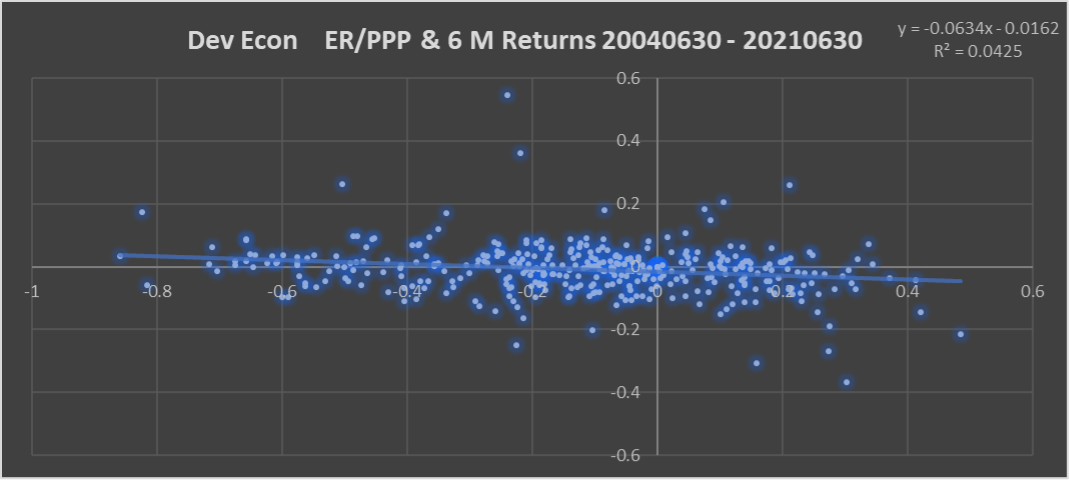

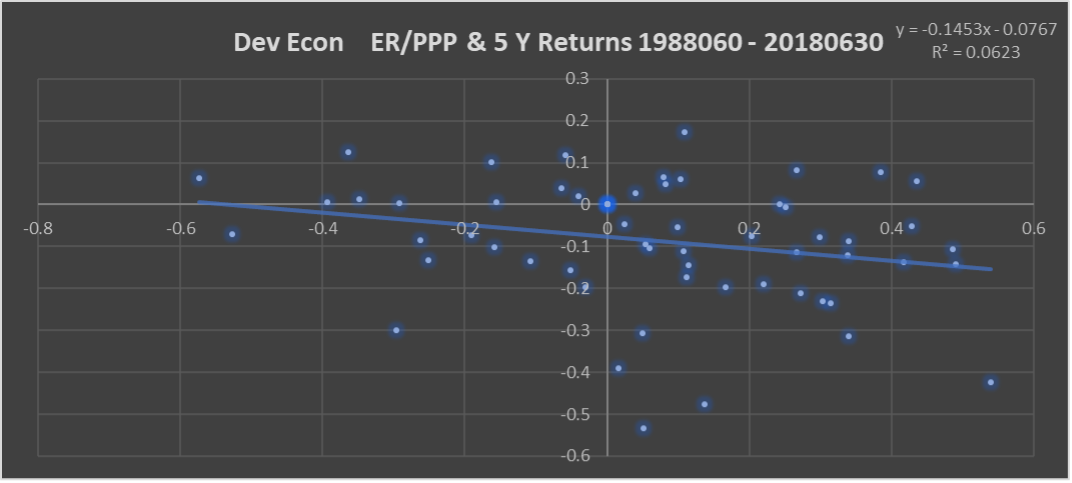

The fundamental value of any currency can be assessed by measuring the value and quality of the goods and services that it can be exchanged for. In the absence of transaction costs exchange rates should converge to equilibrium values that equalize the cost of equivalent goods and services across economies. This is referred to as Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and follows from the law of one price. In practice different economies consume goods and services that are not always directly comparable and transaction costs are often difficult to quantify. These difficulties have led to data quality problems, particularly when looking at smaller economies and data collected in earlier periods. The following charts look at 6-month and 5-year return results for first our total set and then only our developed economy set. The higher quality signal found for developed economies is clear.

The PPP factor signal is much stronger when examining only developed economies. Measurement error explains some of this difference.

CLCI has produced and maintains a proprietary dataset to support ongoing Purchasing Power Parity research. Careful consideration has been given to ensuring that only data as was available at the time is included in the history.

Menkhoff, Lukas and Sarno, Lucio and Schmeling, Maik and Schrimpf, Andreas, Currency Value (June 25, 2015). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2492082 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2492082

Structural Factors

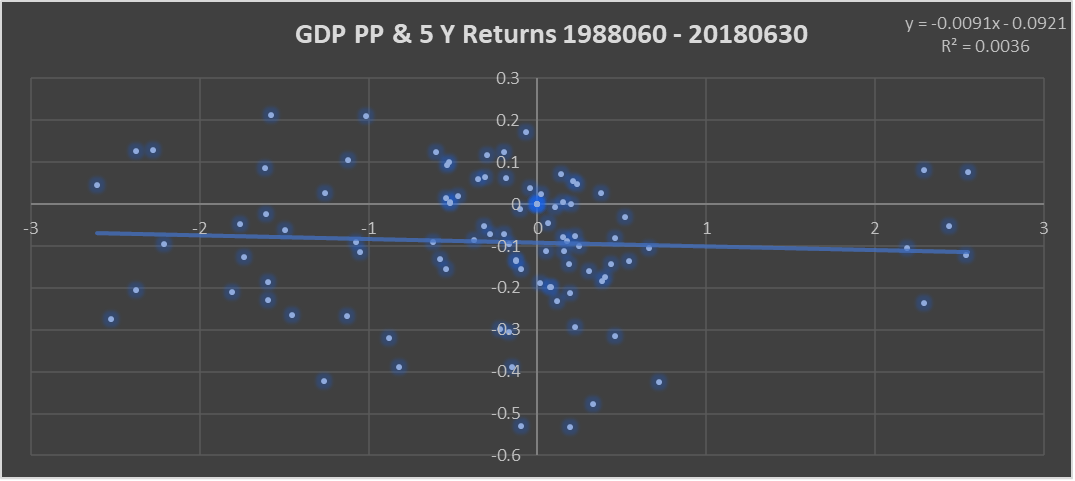

An economy that is relatively less developed as measured by GDP per person should be able to improve productivity at a relatively greater rate than already developed economies by modelling improvements on what has already been shown to work in more advanced economies. If it is assumed that other factors are held equal, then this improvement in productivity should lead to an increase in the value of the currency over longer periods. In practice of course nothing is held equal and as the chart below shows the relationship is weak. One can also observe that the relationship is weakened by the relatively good performance of the more developed economies. Presumably this is related to the higher levels of monetary discipline in developed economies moderating inflation shocks.

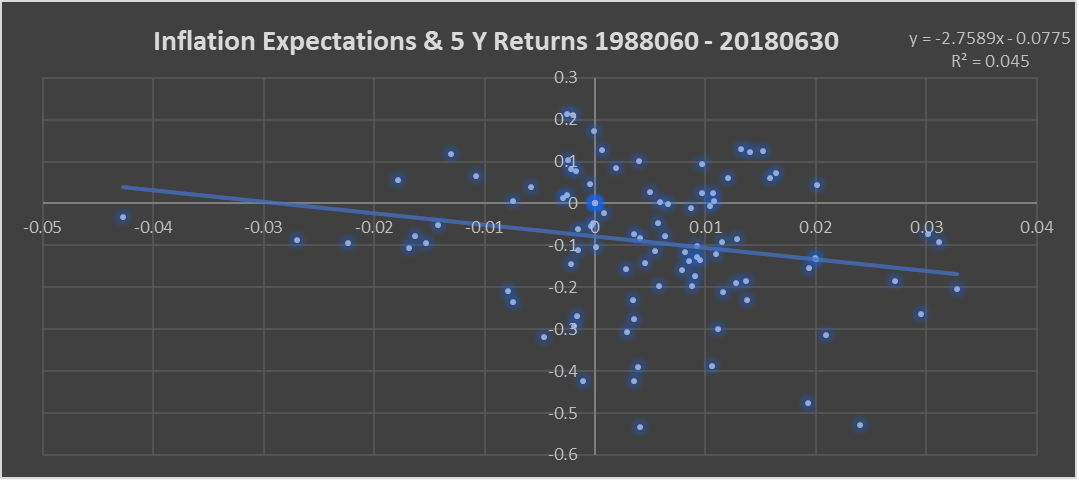

Market derived relative inflation expectations do indeed display the expected relationship with future long-term currency returns.

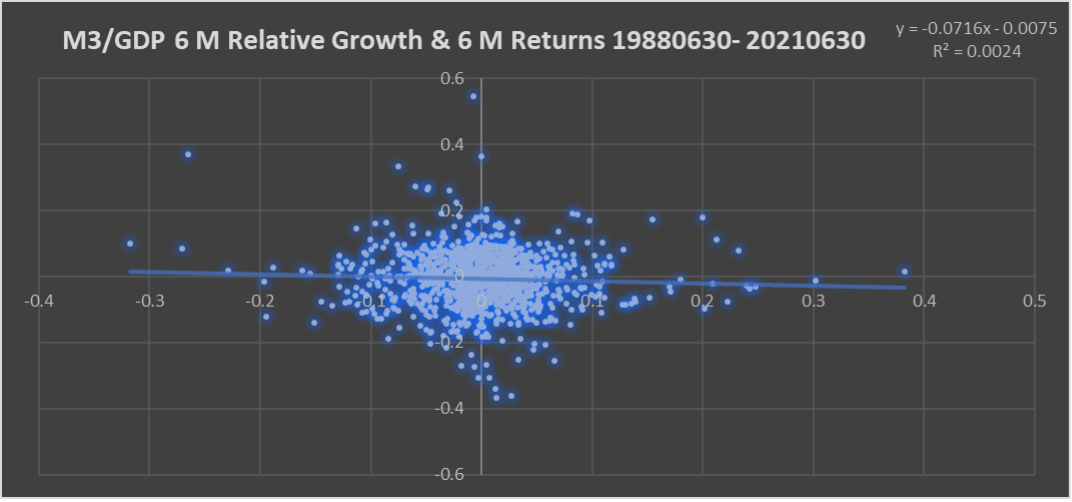

Money supply growth also displays the expected relationship with future returns.

Putting it all together we derive a model from fundamental economic principles that has been stable throughout the sample period.